Originally published by Middle East Eye

The results of the recent Israeli election indicate that another far-right government coalition will be formed under the leadership of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who campaigned on a promise to annex the West Bank.

As with all previous Israeli governments, the expected Netanyahu-led coalition will continue to suppress the Palestinians, but this time it may do so without rhetorical and policy reference to the Oslo Peace Process and “occupation”.

In so doing, any distinction between the territories that Israel occupied in 1967 and was established on in 1948 will rapidly disappear.

Occupied no more

The US has already paved the way for such a future. Recently, the US administration stopped referring to the West Bank, Gaza Strip and the Syrian Golan Heights as “occupied territories” in its annual human rights report.

This was preceded by President Trump’s recognition of Israeli sovereignty over Jerusalem in December 2017 and then the Golan Heights, which Saeb Erekat, a senior Palestinian official, considers a prelude to recognising Israel’s annexation of the West Bank.

To be sure, previous US administrations have already conceded that parts of the West Bank, the so-called Jewish “settlement blocs”, must be annexed to Israel.

Israel conquered and occupied the West Bank, Gaza, East Jerusalem and other Arab territories like the Golan Heights in June 1967. Since then, the international community has labelled those areas “occupied” under international law.

The Trump administration has though displayed a willingness to forego international law in its foreign policy, aligning itself fully behind the Israeli project to colonise the entirety of historic Palestinian.

Since conquering the Palestinian territories in 1967, Israel has violated the rules of occupation stipulated in the 1907 Hague Regulations and the Fourth Geneva Convention. It has operated as a settler-colonial state, which wants a conquered land without the original people on it.

This aim can only be achieved through the elimination of the indigenous presence from most of the land, in violation of international law.

Elimination is the settler-colonial state’s guiding principal, purposed as “a sustained institutional tendency to supplant the indigenous population”.

Israel took this approach from the start of its own “state-building” in Palestine, when it eliminated much of the Palestinian presence on the land.

In 1948, it seized 78 percent of Palestine and forcibly expelled over half of the native population (about 750,000 people) and destroyed more than 500 of their villages. On that land the settler-colonial state of Israel emerged.

After an aborted 1956 foray into Gaza during the Suez Crisis, Israel again expanded in 1967 and took the remaining 22 percent of historic Palestine: the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem – known as the Occupied Palestinian Territory, or OPT.

There, Israel followed a 1963 plan to conquer and enforce military rule over the OPT. This time though it did not succeed at immediately driving as many Palestinians off their land and has instead taken a different approach to reducing the Palestinian presence to make space for Israeli settlers.

Occupation versus colonisation

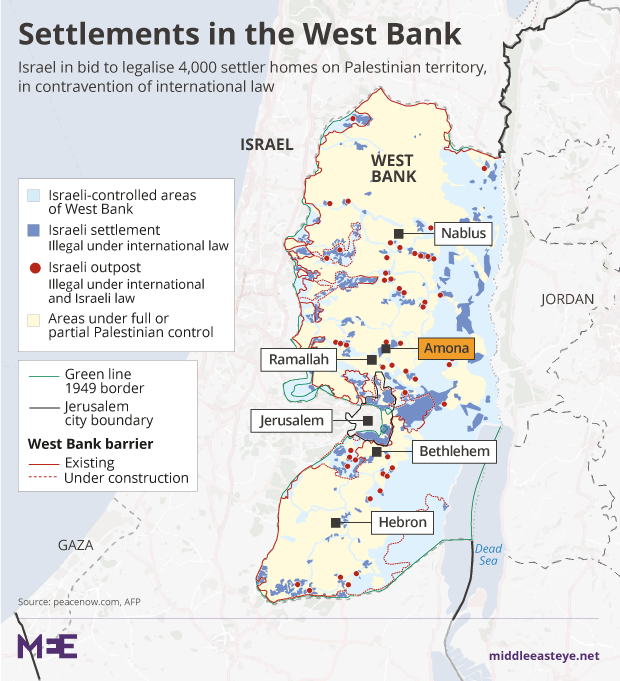

Starting in the 1970s, fervent settlement construction and a network of settler-only bypass roads began to push Palestinians into specific “areas” of the OPT. This paved the way for further land expropriation and, paradoxically, this model of dispossession came to operate in parallel with the peace process and “state-building” programme in the 1990s.

There Palestinians were corralled into ever more shrinking spatial territories, discursively re-labelled Areas A, B and C within a neo-liberal paradigm of peace and negotiations.

Encircled by ever more settlements, bypass roads and the Separation Wall, each area (i.e. Palestinian town or city) has been blockaded into a gated enclave with Israeli-controlled entrances and exits that Israeli forces close or open at will.

This has allowed Israel to complete a spatial redesign of the entire OPT into a gigantic matrix of control. There Gaza has been tragically transformed into the world’s largest open-air prison, and the West Bank a “swiss cheese” of smaller and isolated open-air prisons and enclaves.

So, without resorting to the blatant mass expulsion of Palestinians carried out in 1948, Israel has effectively been eliminating the Palestinian presence from the majority of the OPT by restricting their presence to specific controllable and gated “areas”.

Those areas encompass an extremely small percentage of the original Palestinian land, with Israeli settlers brought in to populate land the Palestinians are removed from.

Yet, despite clear evidence of settler colonial practices in Palestine, and the use by most of the international community of settler colonial terminology like “settlements”, “land expropriation”, “population transfer”, “separation wall”, “frontier” and “settlers”, most observers – particularly in the West – still tend to discount settler colonialism as a thing of the past.

Legal and political cover

In October 2009, by acceding to an “agreed on outcome” that would permit ongoing Israeli settlement expansion, the Obama Administration buried the two-state solution that the peace process is built upon.

At the same time, the narrative of occupation, discursively packaged alongside the two-state settlement and political process, granted Israel legal and political cover to continue with its settler colonisation unabated.

In this way occupation has been useful as a term employed conceptually to reinforce the hollow paradigm of a negotiated settlement, while the last bits of the OPT are settled and annexed into Israel.

This narrative also allows the international community to avoid taking the hard but necessary steps of enforcing international law, supporting democracy and defending human rights, while providing them with a faux framework to craft policy for an alternative reality that does not exist.

Further, this framework has fragmented the Palestinians, altered their political priorities and put their resistance against dispossession into disarray. Meanwhile, it has provided some Arab and Western states with an alibi to continue normalising and strengthening their relationship with Israel, so long as there are “negotiations” to end the occupation.

While one Israeli political leader after another declares they will not give up control over the OPT, the Trump administration aims to end the Palestinian struggle for self-determination, and the right of return for Palestinian refugees, by discontinuing use of the term occupation as part of the “deal of the century”.

Yet, this also exposes how deeply false the narrative of occupation, a two-state solution and a negotiated settlement have become.

Colonial elimination

For generations now, Israel has been engaged in colonial elimination. Whereas occupation is characterised by temporariness, the process of settler-colonisation and elimination are permanent.

So, a deepened cooperation between the Trump administration and Netanyahu governments over the annexation of Palestinian lands is inadvertently offering a chance to reframe the OPT as colonised, not occupied, further doing away with the artificial distinction created between Palestinian territories conquered in 1967 with those from 1948.

This offers an opportunity to rethink the nature of the Israeli-Palestinian struggle as one of decolonisation for all of the peoples in the entirety of historic Palestine.

Such decolonisation would be the first step towards building a shared future based on humanity, justice, equality and democracy for all.

Cited as: Badarin, Emile and Wildeman, Jeremy. 2019. Rethinking the nature of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Middle East Eye, 11 April.